The process we inherited

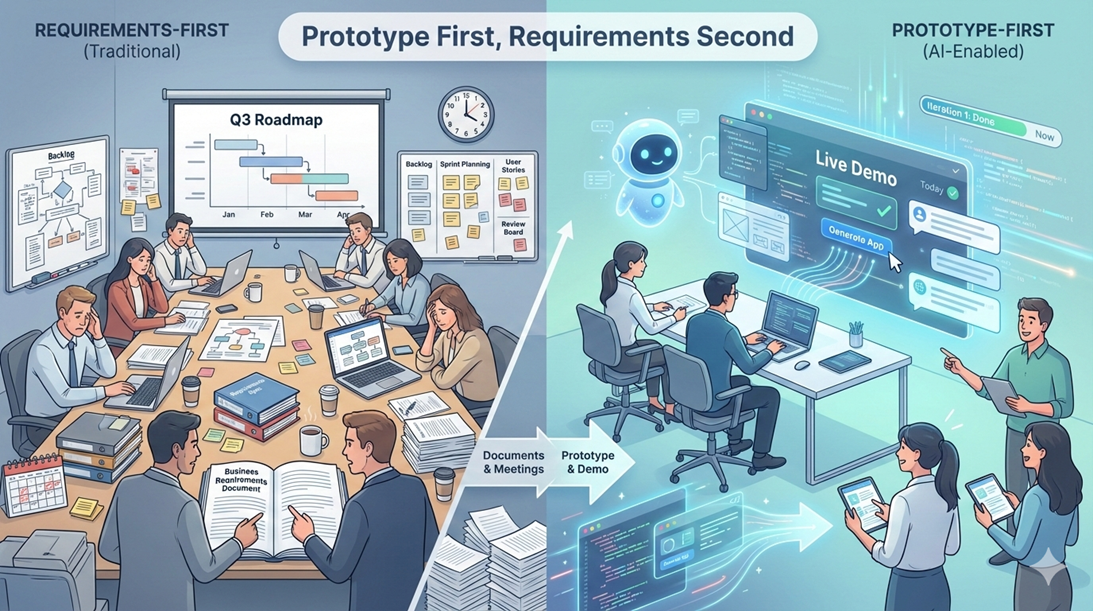

I have been rethinking how we clarify requirements in software teams, because the way most of us still work feels optimized for a world that no longer exists. Traditionally, we treated requirements as something that had to be settled before implementation began. We wrote documents, scheduled planning sessions, debated edge cases in meetings, aligned on tickets and estimates, and only after everyone felt comfortable did we finally start building. That process made sense when writing software was expensive and slow. If a feature took weeks to implement, investing time up front to reduce mistakes was rational.

With agents, the economics have changed enough that this logic deserves to be questioned.

The bottleneck has moved

Today, spinning up a working demo often takes hours, sometimes even minutes. A rough but functional version of a workflow or feature can usually be generated faster than a requirement document can be written and reviewed. In many situations, it is simply easier to vibe code a prototype than to describe the same idea clearly in words. Yet many teams still default to long requirement discussions and alignment meetings as if implementation were the dominant cost. We are still behaving as though building is expensive, when in practice the most expensive part of the process has quietly shifted somewhere else.

Execution is no longer the slow part. Clarification is.

Most of the delays I see now are not caused by coding effort, but by ambiguity. What exactly are we building? How should this flow behave? Which edge cases actually matter? Documents do not resolve these questions as effectively as we assume, because they remain abstract. Everyone reads the same specification and imagines a slightly different system. The team may feel aligned in theory, but the first real demo almost always exposes gaps in understanding. Something behaves differently than expected, or a missing step suddenly becomes obvious, or an assumption that looked harmless on paper turns out to be critical. At that point, the document no longer helps much, and the conversation resets around the thing that always should have been central: the working software.

Why prototypes align better than documents

A prototype changes the nature of alignment because it collapses interpretation. When people look at something concrete, the discussion moves from debating language to reacting to behavior. Flow problems become visible immediately. Missing data or integration constraints surface naturally. Stakeholders respond with specific feedback rather than general opinions. In practice, a short live demo often produces more clarity than hours of meetings.

Agents make this approach cheap enough that it can become the default rather than the exception. They can scaffold a basic UI, mock APIs, generate test data, and wire simple logic almost instantly. The goal is not polish or production quality at this stage, but tangibility. You simply need something real enough that people can reason about it together. The prototype becomes a thinking tool, not a deliverable.

A more effective workflow

There is also a practical process implication here. Instead of trying to perfect requirements before any code exists, it is often more effective to treat development as two deliberate iterations with different goals. In the first iteration, the objective is alignment rather than completeness. You build a lightweight prototype quickly, use it to surface assumptions, gather feedback across teams, and clarify what actually matters. In the second iteration, you take those concrete learnings and build the production-grade version with the right details, constraints, and edge cases already understood. The first pass optimizes for learning and speed, while the second optimizes for robustness and quality. Separating those goals reduces wasted effort and makes both iterations more efficient.

Interestingly, the prototype does not just help humans align with each other; it also becomes a clearer instruction for the agent itself. Instead of feeding the agent a long requirement document and hoping it interprets the intent correctly, you can point to a working example and say, “take this and make it robust, scalable, and production ready.” A concrete artifact communicates intent far more precisely than paragraphs of text ever could. In that sense, the demo becomes executable intent, which is exactly the kind of input agents respond best to.

Rethinking where we spend time

Taken together, this suggests that the traditional order of operations should probably flip. When execution is cheap, building becomes one of the fastest ways to think. Continuing to rely primarily on documents and meetings simply preserves friction that no longer needs to exist. If the cost of a quick prototype is lower than the cost of another alignment meeting, then the rational choice is to prototype more and debate less. In the AI era, the most expensive thing we still do may be meetings, while the cheapest thing we can do is generate something real and learn from it immediately. That shift alone changes how we should approach requirements and planning, and it is likely one of the simplest ways to make teams move meaningfully faster.